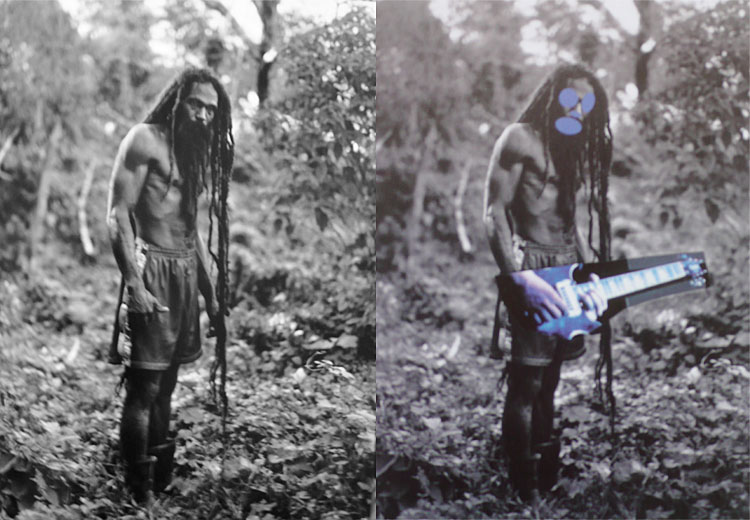

This week our coursework looked at copyright and referred to the well documented copyright case of Cariou vs. Prince. French photographer Patrick Cariou opened a case against Richard Prince and his gallery, Gagosian, for copyright infringement. Prince, a well known appropriation artist had incorporated some of Cariou’s images from his book, Yes, Rasta, published in 2000, into his series of paintings and collages called Canal Zone, exhibited in 2008 at New York’s Gagosian Gallery .

The outcome of this landmark case in 2009 initially found in favour of Cariou, but then on appeal in 2013, found that Prince, the defendant, was free of any copyright infringement and this decision was based on the principle of ‘Fair Use’. Both the Warhol Foundation and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation had filed briefs in the appeal case siding with Prince. “Their argument: the intellectual content and aesthetic meaning of works of art are not always visible to the naked eye without art-historical context. Their brief suggested that art historians, curators and other experts should have a say in the case”. (Boucher, 2019)

The principle of fair use, stipulates that the secondary use of an image must transform the original by using it in a different way or for a different purpose in order to create a new meaning, or message. “Whether or not art is transformative depends on how it may “reasonably be perceived” and not on the artist’s intentions. Even though Prince expressly stated he did not “have a message,” the court still found that most observers would see Prince’s “Canal Zone” as having a radically different purpose and aesthetic than Cariou’s “Yes Rasta” and that this was enough to make the work transformative”. Artist Rights. (2019)

This raises the question of what is considered ethical as there are a number of factors to be considered in this case, such as the financial impact – Prince made a significant amount of money with his series of ‘Canal Zone’, while Cariou as the original artist did not make much through the sales of his book. It raises the question of whether the appropriation of the images may have had a negative impact on the marketing of the original work.

Another important factor to consider is the length of time taken by the original artist to create the body of work. In Cariou’s case it took 6 years to create this body of work during which time he lived and worked alongside the Rastafarians in Jamaica building up the trust necessary to allow him to photograph them. Lastly, and most importantly, in the context of the Cariou vs. Prince case, I believe the question must be asked whether the subjects of the artwork were treated ethically and how they may have felt about the appropriation and subsequent use of the images.

In conclusion, this case highlights the fact that although the use of copyrighting indicates ownership of material, it doesn’t necessarily protect work from being utilised or re-purposed. If copyrighted work is used without permission, there would be legal grounds to open a court case to defend the work based on the copyright laws of a particular country. This would largely depend on whether or not one could afford such a case and then, should such a case goes to court, Fair Use would be applied in countries such as the USA and UK.

References:

Boucher, B. (2019). Landmark Copyright Lawsuit Cariou v. Prince is Settled. [online] ARTnews.com. Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/landmark-copyright-lawsuit-cariou-v-prince-is-settled-59702/ [Accessed 3 Dec. 2019].

Artist Rights. (2019). Cariou v. Prince — Artist Rights. [online] Available at: http://www.artistrights.info/cariou-v-prince [Accessed 3 Dec. 2019].