The context in which we both create and consume photography is constantly changing and transforming, opening up new possibilities and directions.

Price, 1994, states that the use of the photograph determines it’s meaning. In other words, the context in which we view the image determines its meaning. This is illustrated very well in the Benneton Advert which formed part of their controversial 1992 ad campaign which used an image by journalism student, Therese Frare, originally published in November 1990 LIFE Magazine. The original black and white image was of gay activist and AIDS victim, David Kirby, as he lay on his death bed. Two years later this image was recolourised by artist Ann Rhoney and used by Benetton in its campaign.

Concept: Oliviero Toscani Photo: Thérèse Frare Source: http://www.benettongroup.com/

Different groups had different reactions to this image, however, it received a lot of heavy criticism and backlash as it was perceived as spreading fear and profiting from the suffering of others. Yet David Kirby’s own parents had consented to the use of this image, as did the photographer, who believed this was a powerful message to raise awareness. Benetton themselves stated that this was the first public campaign to address AIDS and was intended to show solidarity. It is obvious there were different perceptions surrounding the way the image was portrayed.

Benetton often used pseudocumentary style images in their advertising campaigns and many of their adverts have been highly controversial, drawing different responses from different groups of people. Their campaigns often need to be looked at on a deeper level to understand the meaning. I don’t personally find their images offensive, instead I view them as provocative and challenging, inviting the viewer to connect with the concept and engage with it.

Reaction could thus be considered a success as it has evoked emotion and engagement. More thoughtful analysis of their adverts, however, would lead to a response rather than a reaction. Their campaigns certainly illustrate how meaning can be interpreted by the viewer and also by the context in which the image is placed. These images were likely to have been judged much more harshly when viewed as advertising and seen in the context of magazines, than if they were seen in the context of documentary photography or art. More of their historic campaigns can be viewed on their website: Benetton Group.

In looking at my own photographic practice and the context in which it is created and potentially received, I relate very strongly to this quote by Barthes, as it is closely aligned to my own relationship with photography and what I attempt to convey in my photographic practice:

“The photograph is a message. Considered overall this message is formed by a source of emission, a channel of transmission, and a point of reception.” (Barthes, 1977, p.15).

My own practice is located predominantly within documentary style and urban landscape photography, both of which could be consumed through the format of printed photographic images, either as part of a collection, exhibition or individual prints, or within the printed format of a photographic book. No doubt there are other contexts to consider but these are what I feel are most suited to my particular practice.

In considering how my photographic practice may be received and interpreted by viewers, I believe that the context is very relevant and relates to the audience or consumer of the work. An example of context is apparent in the feedback I received for last term’s Work in Progress. The tutors felt it was repetitive in places, and needed more depth and experimentation.

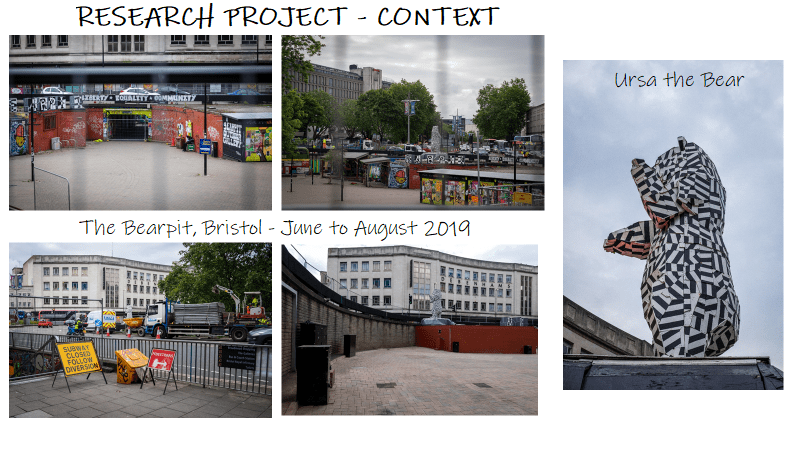

I had shown this work to others prior to submitting the assignment and received different responses from them. What I noticed was that people who lived in Bristol and weren’t photographers all felt a sense of sorrow within the images and knew exactly what the series of images was about. This led to them relating to the images and expressing their own feelings about the space being depicted and the events surrounding the images.

I also showed these images to people who were photographers but didn’t know the story behind the images. Most of them picked up on the narrative by spotting the clues in the images – things such as the changing seasons, the colour yellow and the link to the yellow lines, the strong sense of desolation and loss, and of course the missing bear.

What is very apparent is that there were three different perceptions and sets of responses to the same images based on the context in which they were viewed: critically as part of the MA Photography assignment, emotionally by people who lived in the area and related to the story, and technically by other photographers. This is something I will always need to consider when creating photographic projects and when making decisions about the context in which they will be consumed and who the audience is intended to be.

Resources:

- Barthes, Roland (1977). ‘The Photographic Message’ in Image Music Text. London: Fontana.

- Benettongroup.com. 2020. Benetton Group – Corporate Website. [online] Available at: <http://www.benettongroup.com/media-press/image-gallery/institutional-communication/historical-campaigns/> [Accessed 22 June 2020].

- Price, Mary (1994). The Photograph, A Strange Confined Space. California: Stanford University Press